At long last, Christopher Alexander (C.A.) Fleming, educator and publisher in Owen Sound, Ontario, was embarking on a voyage to the United Kingdom. The year was 1924 when Europe was rebuilding after the war of 1914-18. Roy Fleming, his cousin, had emphatically recommended such a trip after his own in 1903.

C.A. – you know you are rich – you might cease from your labors for two months and take a trip to the Old Country and see these places – see that land of true beauty and sweet traditions – the land of your fathers, which age will never dim. [Letter dated 14 October 1903]

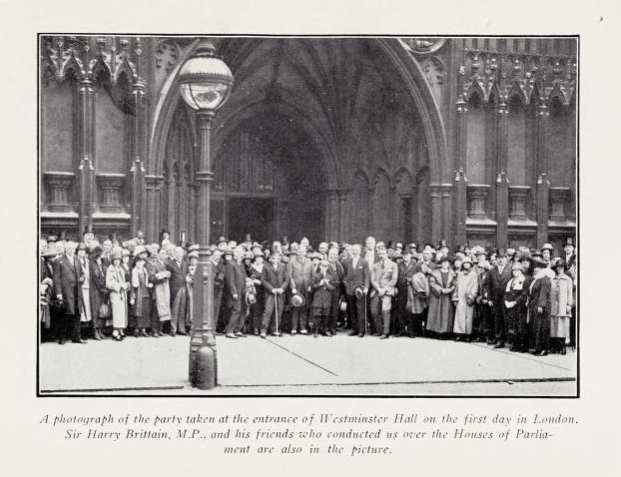

Arranged by the Canadian Weekly Press Association for editors of weekly newspapers, the tour covered Belgium, Paris, and the major cities in the United Kingdom. There were 171 individuals in the party, of whom 101 were associated with some 100 weekly Canadian newspapers. Of these editors, 83 were men and 18 women. Seventy family members travelled with them. Many of the editors were from Ontario, and smaller numbers from the Atlantic provinces and the West. [Davies, “Who’s Who”]

C.A. owned the Daily Sun-Times and the weekly Cornwall Freeholder. His eldest daughter, Lillian, who was 37 and a kindergarten teacher, accompanied him on a trip that became the highlight of her life – especially the garden party at Buckingham Palace.

Over the eight weeks, C.A. mailed letters to the Daily Sun-Times with reports on the social events and the places – the streets, the people, the exhibits and tours. These were dense with descriptions of the farmlands and industrial sites and attentive to points that his Grey County readers would appreciate. He later published his reports as a collection in Letters from Europe.

W. Rupert Davies, of The Renfrew Mercury in Renfrew, Ontario, and former president of the Association, organized the itinerary and meetings with dignitaries and press associations. He published his account in Pilgrims of the Press, in which he explained that this endeavor was to be “an educational tour with the idea, not only of establishing a closer relationship between the weekly editors of Canada and the newspaper fraternity of the Old Land, but in order that we should all get first-hand knowledge of the Mother Country and some of its problems.” [Davies, p. 3] (Davies, who many years later was appointed to the Canadian Senate, brought his wife Florence McKay and their son Robertson – the Robertson Davies who grew up to be a journalist and acclaimed novelist.)

The idea for conducting such an ambitious tour was rooted in a strong sentiment for the British Empire. The elite of the Empire Press Union and the Newspaper Society in England provided full support and likely direction. We might surmise that their motives were to strengthen diplomatic and economic bonds between Canada and Britain. Notwithstanding that Canada had just fought for “King and Country,” Canadians were pressing instead for autonomy and independence from imperial requests.

Continue reading