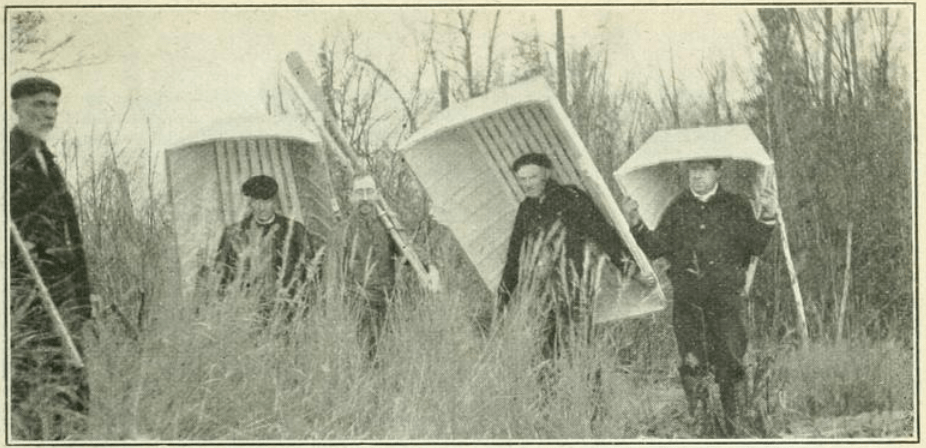

While researching the life of C.A. (Christopher Alexander) Fleming (1857-1945) for the Flemings of Derby Township: A family history, I learned that C.A. had designed and built a boat that could be separated into parts for easier travelling on hunting trips. (1) But I had no further information on shape or size or even usefulness. By good fortune, I came upon an article that C.A. wrote in 1914 describing the boat and wondered if this type of boat is made today.

C.A. Fleming, educator, publisher and banker in Owen Sound, Ontario, was at heart a “master hobbyist,” as we know from his biographer, Dorothea Deans. She drew attention to C.A.’s skills with all tools, adeptness with machinery, and early adoption of camera and radio. “He had the inventiveness of a pioneer,” she wrote. (2)

He was also an avid outdoorsman, travelling into remote areas for hunting with the Striker Club in the late 1800s and early 1900s. My surprise was to find the article he wrote in 1914 in Rod and Gun in Canada in the Internet Archive.

Modestly, he explained in the opening paragraph: “The writer began experimenting about two years ago on boats that could be easily made by any handyman, that were light and tight, easily transported by train or vehicle, easily portaged, stored in a small space, and quite safe for any inexperienced person to handle.; and succeeded in building one that filled the conditions aimed at.” (3)

In the article, C.A. gave detailed instructions and parts lists for constructing a 13-foot-7-inch boat with a 42-inch beam weighing about 90 lbs. It could also serve as a motorboat with the addition of the Waterman outboard motor.

C.A. claimed that taking the boat apart was nearly dead simple: “… [I]t was very little trouble to take apart —we had only to take out eight bolts and separate it into three sections. We found no trouble in carrying it back two miles through the bush to a lake where the deer were taking to the water. The portable boat and the portable engine made a fine combination for the hunting grounds.” Being in segments, the boat, he found, was easy to load onto a train, could be packed with camping goods, and could be carried in portages.

Continue reading